GNSS TimeReceiver

| Project GNSS Reradiator | |

|---|---|

| |

| GNSS reradiator to receive GPS, Galileo L1/E1 indoors | |

| Status | In progress |

| Contact | User:cmpxchg |

| Last Update | 2020-04-19 |

What is a GNSS / GPS re-radiator or -repeater ?

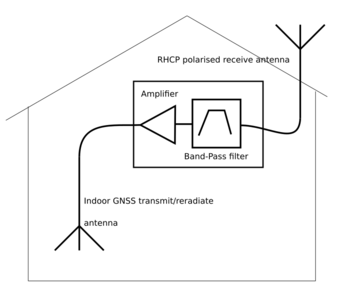

An Indoor GNSS re-radiator uses an indoor, in-room antenna, to transmit a low-power GNSS signal that is a copy of a GNSS signal picked up on the roof. The signal is intended only for devices present in the room.

What is a GNSS Time Receiver ?

The receive antenna and cabling of a repeater-system can also be used to directly feed a GNSS, GPS or Galileo Time Receiver placed indoors.

For such coax-cabled receiver, no re-radiating antenna is needed, but a similar installation is needed to get an accurate copy of the GNSS signal indoors.

Application of GNSS Re-radiators

One application of GNSS Re-radiators are fire- and ambulance services, vehicles parked inside a garage, without a direct view of the sky.

Without a re-radiator, they will typically not be able to receive GPS or GNSS signal in a reliable way.

The ReRadiator will wirelessly, via the same frequency, keep the cars/devices supplied with current GNSS RF data.

This way, the latest orbit and clockinformation will be available before and up to when they leave the garage.

Leaving the garage might cause a slight change in level of the signal, and phase will also change slightly, small enough to be picked up almost effortlessly by

the signal correlators in the GNSS receiver.

In contrast, if the GNSS acquisition could only start when leaving the garage, it would be much harder, especially on a fast moving vehicle in a city.

Acquisition would take at least 30 seconds if not provided with recent GNSS / GPS RF data and synchronized clocks.

Why are 4 satellites needed to calculate an accurate GNSS position ?

Intuition would say just 3 spheres, indicating a range from each of 3 GPS satellites, should be enough to provide a unique, earth-height, intersection.

In practice, 4 satellites are used, and 5 in some RTK (real-time kinematic) applications.

The PVT (Position, Velocity and Time) calculation involves pseudo-ranges to four satellites, each path is refracted

(slightly) differently through the atmosphere. This 'bent' path creates an error that is dependent on weather, elevation of receiver, and angle (elevation) to the satellite.

Using less than four, the error would be too big, and does not lead to the about 7 to 12 meter accurate position that is expected by GPS/GNSS users.

Also, the local clock offset must be determined, which can be calculated more accurately through the use of the fourth satellite in the equation.

GPS-RTK systems use a static receiver that will provide a model to a nearby rover receiver to compensate for these errors, this works for a range of a few to tens of km.

Another thing RTK receivers do, is resolve the integer number of wavelengths between the antenna and the satellite, so that a precision below the wavelength, 19cm, can be obtained.

Resolution can be divided down to:

1 bit of 50 bps - 20 msec, or

1 light-msec -

What GPS/Galileo/GNSS updates can I receive with an indoor replica of the GNSS signals ?

The updates to the satellite orbits and clock drifts are continuously transmitted by each GPS or Galileo satellite.

GPS 'broadcast ephemeris' data is valid for 4 hours and is updated every 2 hours, and contains exact information on the orbit

and position within that orbit (Keplerian parameters). It also contains a clock offset relative the the GPS master clock maintained

at a central location on ground.

The 'Broadcast ephemeris' part of the signal is unique to each satellite and is broadcast in 18 seconds, and transmitted every 30 seconds.

This three times 6 second 'frame' period aligned to each half-minute is the reason that almost all GPS receivers have a cold-start of a little

over 30 seconds (signal acquisition and receiver turn-on time alignment might be variable)

GPS Almanac data, and things like UTC offset is also transmitted by each GPS satellite, over a period of 12.5 minutes, using the remaining

12 seconds of the 30 seconds period.

The GPS Almanac and is is a map with coarse information of all (other) GPS satellites that might not yet be visible on the sky but could

be tried to be acquired, for example to replace one that just went out of view.

The initial GPS Almanac also comes in ROM of a receiver, and might get out of date as satellites are replaced after many years. It

it typically also saved into SRAM and flash memory of the receiver.

Note that there is no dependency on internet for either GPS Broadcast Ephemeris data or GPS Almanac data.

All data comes from the same source, the satellite, and is synchronized up to the nanosecond level.

A receiver without any idea of time, can just start looking for a random PRN code (CDMA code number, 1-37), find an SVN code (satellite

vehicle number), and start tracking it. Over a periode of 12.5 minutes it can download all other PRNs and SVNs, and determine

the right PRNs to look for at the approximate location.

Receivers do not have clocks that are compact, good and low-power enough to maintain precision on nanosecond level over many hours,

Typically, a 32 kHz clock is available with a precision of a few milliseconds. A-GPS pretends to use a mobile network-provided

clock, which is also slaved to GPS, to provide accurate time to receivers, but that would only work in a smartphone-like enviroment,

which most GNSS/GPS modules are not. Maintaining or connecting to a GSM like network costs a significant amount of RF power and

interaction.

Initial absence of a fast and precise time is not really a problem for GNSS modules, they can compensate with cheap compute power,

and dedicated correlator hardware in a cheap and low-power CMOS process. CPUs have limited use, they are not good for many 1 or 2-bit

multiplications/lookups. Since the digitized I/Q data is just 1 or 2 bits, correlation over a many thousend samples involves lookups

with a known local PRN sequence, and many adds.

The receiver will search in the noise (a few milliseconds to seconds on modern receivers) for a potential visible PRN, and

synchronise until it finds a HOW, handoverword, which passes by every 6 seconds. After this, in 30 seconds, it can pull in the most

recent Broadcast Ephemeris data.

Some receivers allow prediction of orbits using pre-computed/extrapolated data, 'quickgpsfix' - but this data needs to be confirmed when the real

data comes in after 30 seconds.

Navigation and timing receivers, receiving a re-radiated GNSS signal, can acquire a position indoor, but will calculate an

position that approximates the location of the rooftop antenna.

It is not possible to calculate one's position within the room, only the range to 'the' or 'one of' the GNSS ReRadiators can potentially be calculated.

For this, information on the delay of the antenna, amplifiers, cables and filters is needed, which is not, or not directly, part of the re-broadcasted, analog RF signal.

What happens in the GNSS receiver with a 'ReRadiator' signal source instead of direct-sky, own antenna, is an apparent pseudo-range 'bias' of all (typically 4) satellites

that end up in the positon/velocity/time solution (PVT).

If this 'common bias' in pseudo-range is assumed zero, it will result in a calculated position that is 'deeper' than the roof antenna, and offset opposite to the side where the

highest-elevation satellites are present at that moment. Having a position below earth should not be a big problem, it will resolve to an above-earth position on a map. Height will be much less accurate compared to latitude/longitude with GNSS signals anyway.

Almost all receivers will default to the highest elevation satellites that are received, since they have the least amount of range-errors introduced by the atmosphere,

and such radio-path are generally free of obstacles and reflections. In addition, reflections via a flat surface will invert the polarity of the circular-polarized signal, causing losses in well-designed polarized GNSS receive antenna's

How strong are ReRadiated GNSS signals?

If the power level is kept close to the specified -128 dBm outdoor level (GPS), it will not escape the room.

GPS is specified in the publicly available Interface Control Document, ICD GPS-200D (or later), at -158.5 dBW or -128.5 dBm receive level on earth, with a 3 dBi isotropic receive antenna, basically an antenna that only picks up signals above it, and not below it, and thus doubles the 'gain' compared to an globe-shaped idealized omnidirectional antenna.

The power is equivalent to about 100 attoWatts, 0.1 nanoWatt, or 0.0001 microWatt, or 0.0000001 milliWatt. It is so small that one has to know the signal so that it can

be recovered by correlation. The thermal noise level for that bandwidth is many dB's above this, the signal is invisible on a spectrum analyser.

Yet, one does not have to cool one's antenna to a few kelvin, like some radio astronomers do to get their radio-pictures of galactic objects.

By comparison, mobile telephones can produce peaks of 2 watts, or 33 dBm. Compared to -128.5, this is a difference of 161.5 dB, a voltage factor of almost 200 million.

At first sight, it is almost a miracle that the weak GPS signal does make it through.

There are a lot of tricks used to make it work, and makes a nice example for both science and signal processing.

Another nice aspect of GNSS systems, is the efficiency at which it operates.

With 24 satellites each producing 27 watts of RF power, a total of just 864 watts, less than a vacuum cleaner, everyone on earth can determine their own position down to a few meters, and even do that without having to reveal their location or identify oneself.

If one compares that with many-watt's-each mobile service base stations, spread over all urban area's in the world, it is the most efficient globally deployed radio service ever invented. Another remarkable fact is that is an open service, available to all, operated by the US Air Force.

Compared to domestic wifi accesspoints and wifi devices, it is also impressive. WiFi receivers minimum level is about -98 dBm, about 30 dB less sensitive as GPS.

Wifi outputs a factor 1000 more power for the weakest link of about 1 megabits per second, and often a factor million more to have a reasonable speed op 54 mbps.

Wifi also uses a different frequency, one intended to be used for cheap and leaky microwave ovens, 2400-2480 MHz.

The bandwidth (occupied frequency range) is about 22 MHz, for GPS it is around 2 to 3 MHz worth at 1575.42 MHz centerfrequency.

The GPS satellites output each ca 27 watts towards earth on the L1 frequency (1575.42 MHz, ca 2 MHz wide). The temperature of the antenna is very low. After this the signal

travels ca 22000 km, and arrives at a GPS receiver antenna in about 77 milliseconds. These L1 are the only signals that a re-transmitter should transmit.

There is a significant amount of gain needed, many tens of decibels, and this has to be gain with a very low noise-figure, i.e, as few random, uncorrelated noise added by the signal chain.

The source of the ReRadiator is a point-source receiver, hopefully with a well-defined phase center of the signals arriving from the various directions.

This accumulates only a few square millimeters to many square centimeters of the radio signal, hopefully picking up only sky-sourced radio signals.

This tiny GNSS signal needs to be spread out, still in spectrum-analyser-unobservable noise form, over the room via the re-radiating antenna.

No more than 20 or 30 dB per gain stage is possible. After each stage, filtering is needed to prevent out-of-band signals being amplified,

that will be picked up in some amount (-20 dB or more) by the antenna.

Out-of-band unwanted signals, for example, a nearby GSM modem outputting up to 2 watts in the range of 700-900 MHz, will be much stronger than the GPS signal.

Computers, DRAM memory busses or monitor cables can also leak high-frequency information (EMI), whose (mostly odd) harmonics (1x, 3x, 5x, 7x the source frequency) can end up

in the GNSS band of 1575.42 MHz, which is ca 2 MHz wide, and a few MHz wider if filters have to be taken into account

Unwanted strong signals could, worst-case, saturate the input stage, applying signals that go toward the voltage rail in the first or one of the following amplifier stages.

Next to that, lower level interference can also distort due to unavoidable non-linearities in the RF amplifier, which creates mixing products within the band of the GNSS receiver,

These cause leakage of additional, unwanted, noise in the amplifier output.

It can also trigger automatic gain control adjustment in the receiver, trying to keep the apparent noise within bounds.

Such noise reduces the chance that a zero-crossing resulting into a digital bit going to the correlator, will not be detected, and correlation or carrier-to-noise ratio will decrease, or tracking of the satelite will be (temporarly) lost.

Why is an 'active antenna' needed ?

The 'noise figure' of the first amplification stage is the most important, since that noise will dominate the noise-figure of the complete chain. See Wikipedia, Friis formula for noise. The first amplification stage will always be right behind the antenna itself, before any cable or other element with non-perfect impedance matching and attenuation.

The only thing in front of the first gain stage, or in between two stages, is a filter to supress out-of-band signals. For this, often SAW filters are used, Surface Acoustic Wave filters. These tiny electro-mechanical devices provide enough attenuation outside the designed frequency, while providing ample insertion loss in the pass-band. They are mechanically stable and provide reproducible results.

How is an 'active antenna' powered ?

An 'active antenna' will not radiate signals back via the antenna to the environment. 'Active' means it will amplify the signal before transmitting it down a cable to the receiver.

The power needed for this is relatively small for a wired installation, a tens of milli-Ampere. For ease of installation (no second cable for 'just some power'), it needs to be provided by the device/receiver at the other end of the cable.

The active antenna has a circuit to pull the DC signal from the cable, and will transmit an RF signal, around 1575.42 MHz, upstream to the indoor receiver and powersupply.

The upstream-device needs to provide a DC bias to it's input.

This is similar to how Satellite receiver LNB's are powered. An inductor will provide a DC signal of 3.3 to 5 volts to the

center conductor of the coaxial cable. The inductor passes DC, but will block RF. The RF can pass via a series capacitor, to a receiver's gain stage or filter.

To be inserted: Schematic of DC bias

GPS patch antenna's with a magnetic base are cheap and almost always have one or two gain stages and filters built-in

GPS and Galileo space segment, orbits and signals

GPS satellites orbit the earth in a little less than 12 hours, the aim is half a sidereal day. Galileo satellites use a higher orbit and orbit in around 10 hours.

Towards the poles one will find more GPS satellites near the equator. Glonass has better coverage of the poles, but a lower chance of direct-overhead satellites near the equator,

All GPS satellites transmit on several L-band frequencies, but the L1 signal on 1575.42 MHz is used by 99% of all receivers.

GPS and Galileo signal: CDMA in BSPK and BOC form

The L1 (1575.42 MHz, equals E1 in Galileo parlance) signals of the 24 GPS satellites are transmitted by using a BPSK stream of chips,

at 1023000 chips per second, or about 1 msec per sequence-cycle of 1023 chips. This is called CDMA, Code Division Multiple Access,

which can take many shapes, even a north-American phone standard is named after this modulation principle.

CDMA means a repeating bit-pattern, or better, 'chip' pattern, where the sign of all the 'chips' in the sequence are inverted once in a

while, in order to modulate the payload data, or bits. The chip rate is very high, 1023000 chips per second, the bitrate really low, 50 (gps)

or 250 bits per second (galileo)

The GPS signal can be produced with an LFSR, one or two Linear Feedback Shift Registers that produce, together with a few XOR gates feedback

network, a repeating bitpattern of 2^n-1 length, or 1023 bits - ('chips' in CDMA parlance). In GPS this is the XOR of two shorter LFSRs (Gold codes).

A receiver works by generating the known LFSR/CDMA/chips signal with exactly the right frequency and phase, and performs a

correlation with the received noise, over the period of up to 20 milliseconds.

After the search or 'acquisition phase', which can take a few seconds depending on processing power, the signal can be tracked using this simpler setup.

GNSS Signal Acquisition

Acquisition can be done using two methods, DFT/FFT and convolution in the frequency domain, or the simpler, all digital, an exhaustive search with

correlation of a tens of msec, going over a search range of about 35 kHz (expected doppler range and owm frequency offset), with a resolution of

about 0.5 Hz, and a code-offset space, with a resolution of about half a chip of code-offsets,

thus 1023 * 2 = 2046 chips, a table of 70x2046, almost 144'000 tries. The integration period and number of correlators applied in parallel can drastically reduce this time.

This is the reason old (90's era) receivers took very long to calculate a position.

Once acquired, the found correlation peak can tracked by three correlators for each satellite the receiver wants to track.

Three correlators on subsequent half-chips are used, early, precise and late (E,P,L). The height of correlation between the three is used to feedback

a loop that tracks the phase and frequency-drift (Doppler) of the locally generated signal.

Every 20 msec, the correlation peak can also invert - the inverted LFSR signal is transmitted to indicate a 0-bit or 1-bit of the 50 bps GPS signal,

or the 250 bps Galileo signal

How is Galileo different from GPS?

The european Galileo satellite constellation is using a similar concept as GPS, Russia's Glonass and China's Beidou. GPS and Glonass were the first signals, Galileo and Beidou came later.

Russia is using their own frequency and need a different RF frontend, down-converter stage and antenna with sensitivity in the 1600 MHz band.

Galileo and GPS, and also Beidou use exactly the same frequency, 1575.42 MHz ca 2 to 4 MHz wide. Galileo uses 2046 chips instead of 1023 chips per symbol, so only a little more bandwidth is needed to receive both GPS and Galileo with the same RF frontend. This increase in bandwidth has the advantage that resolution can potentially be improved. Even more improvement is possible if another frequency is used, transmitting simutaneously and phase-coherently with the first signal. On GPS, this is the L2 signal. On Galileo, the E5a and E5b signals can be used. For this, a 'Dual' or 'Multi frequency' receiver is used, which features multiple RF frontends, downconverting serveral band coherently, but still sources from exactly the same antenna.

Is it legal to transmit GNSS indoor ?

In the Netherlands, one is required to report and per April 2017 also acquire a license (vergunning) for a GNSS reradiation installation to Agentschap Telecom. This to help track down nearby interference to other nearby GPS/GNSS users.

Since the Re-radiated GNSS signal is still very weak, it will generally not escape via windows or walls to the outside, and it will not become an 'oscillator'.

The rooftop receive antenna should pick up signals from satellites from all directions, except the ones reflected from the ground or

via other buildings or own windows.

Compared to building a complete-to-time/to-position receiver, building a GNSS ReRadiator or roof-based 'GNSS receptor' is a lot simpler, only 'basic' RF knowledge is needed.

There are many cheap modules available that accept a cable-based GPS/GNSS signal, and output a simple lat/lon position, and height.

Some also provide long-term accurate time, in addition to reasonable short-term accurate time (GPS-DO, disciplined oscillator).

Some allow external clock inputs, or have a reference clock output, from 32 kHz timer-based signals to full 1, 5 or 10 MHz outputs.

How does a GPS ReRaditor 'link budget' look like?

In the path between satellite and receiver, there are many gain and loss stages. Next to that, the amount of noise needs to stay as low as possible.

With two formula's by Friis, the Friis transmission equation and

the Friis formulas for noise the performance can be estimated.

The satellite antenna outputs about 27 watts to earth. It is located in space, thus has a very low antenna temperature - much lower than typically used on earth.

How to select and where to mount the GNSS antenna?

The satellite antenna itself is designed so that the amount of power transmitted to the edges of the earth is higher, to compensate for path length and length in the atmospheric part of the path. The signal is RHCP, right hand circulary polarized.

The size of receiver antenna matters, having more area to intercept the weak signal is advantageous. Smartphones have tiny GNSS antenna's, modules already a log bigger, and surveying antenna's can be up to ten centimeters or more.

The Wavelength of the 1575.42 MHz E1/L1 signal is about 19 cm. For precision applications, the antenna must have a well-defined phase center, so that signals from all directions arrive at the same time, also when the antenna is rotated around it's vertical axis.

A large flat metal groundplane helps to prevent signals reflected by the ground from entering the antenna. Placement on the center of a roof can help in this.

When mounting the antenna somewhere in the northern hemispere of earth, obstructions to the south should be avoided, as the GPS satellites' orbits will be mainly in the south. Glonass satellites will have more coverage of the poles.

Where can I read more technical info on GPS and Galileo?

With both GPS and Galileo, a position and time can be gathered, without have to relay this information via a third-party radio network, like the internet, 2G/3G/4G etc.

Next to the official US-provided NavStar documentation, explanation of the system is documented in the following books and information sources:

2007 - Kai Borre - A software Defined GPS and Galileo Receiver

2009 - Frank van Diggelen - A-GPS

2007 - Blog of Michele Bavaro on development on various GNSS / GPS / Galileo / Beidou / Glonass receivers

2017 - Article displaying gratitude after the disappearance of Kai Borre summer 2017

2014 - Navipedia Website maintained by ESA on almost all operating GNSS systems by ESA (Galileo) and others

2017 - Agentschap Telecom aanvraag GNSS repeater per 1 April 2017